Benefits can become complicated. For your own good, here’s what you should know.

Medical schemes undertake liability in return for a premium or contribution. They are required to help their members in obtaining healthcare services and defraying expenditure for such services. The benefits that a scheme may grant must be registered in its rules.

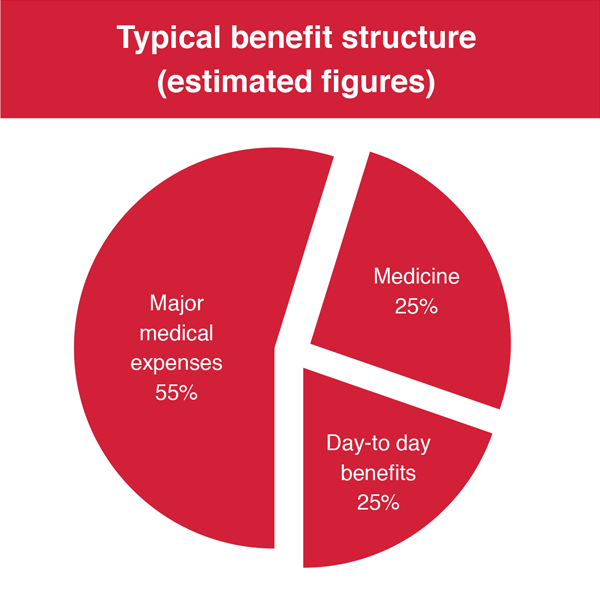

Schemes typically cover the following healthcare services:

- day-to-day benefits: out-of-hospital services and visits to specialists,GPs, dentists and allied and support professionals as well as the prevention, examination, diagnosis and treatment of diseases;

- medicine: chronic and acute medicines; and

- major medical expenses: for hospitalisation, appliances, ambulance services, maternity benefits,and the management of physical and mental deficiencies.

Schemes have the right to control their risk by being effective and efficient as well as using interventions like formularies, pre-authorisation, treatment protocols and designated service providers.

Common tariff structures

A tariff is the rate at which a scheme is willing to pay for benefits. This rate is determined by the rules of the scheme. There are various kinds of tariffs commonly used by medical schemes.

Fee for service (FFS) is based on resources.

The cost of the service reflects the health provider’s investment of time, energy and skills. It is currently the most widely applied payment system in the country.

The National Health Reference Price List (NHRPL) for health services is an FFS pricing schedule published by the Department of Health. Used by healthcare service providers to bill for consultations and procedures,it is a set of guidelines at which schemes should pay for the healthcare services rendered. Most schemes use the NHRPL, and pay varying percentages of the NHRPL depending on the member’s benefit option.

The “per case” tariff structure refers to a single once-off fee for a specific procedure.

It remains the same regardless of the time and effort spent on the medical intervention.

“Per diem” represents each day in which a patient is given access to a prescribed therapy.

Payment ends on the day that the therapy is permanently discontinued. This tariff is used by both the public and private sectors.

Capitation tariffs imply the prepayment for services per member per month. Benefits on a capitation option are limited to the contractual agreement that a scheme has with its service provider(s).

Savings accounts, risk benefits and ATBs

A member’s Personal Medical Savings Account (PMSA) must not exceed 25% of his/her gross contributions made during a financial year. This 25% limit minimises the self-funding by members and eliminates benefit structures that discriminate against members. PMSA funds are used to cover discretionary benefits.

Members with a benefit option that has a savings account may use the available funds to pay for discretionary benefits for themselves and/or their dependants. But PMSAs may not be used to offset contributions or to pay for prescribed minimum

benefits (PMBs). At the end of each financial year, the member’s unused funds are carried over to the next financial year.

Risk benefits are covered by the scheme from the common risk pool where cross-subsidisation occurs (younger and healthier members subsidise older and sickly members). Risk pool benefits include PMBs and in- and out-of-hospital benefits.

Unlike with the PMSAs, unused funds are not carried over to the next year.

Some schemes have Above Threshold Benefits (ATBs), whereby schemes cover expenses over and above a self-payment gap.

Exclusions and limitations

Private health insurance allows people to protect themselves from the potentially extreme costs of medical care if they become ill. It also gives people access to healthcare when they need it.

Health insurance should guarantee access to essential healthcare.

It is a noble idea, but there are threats to the sustainability of private health coverage – one of these is affordability.

Hikes in healthcare and non-health costs, sometimes at rates substantially higher than general inflation, require member subscription rates to increase each year. Schemes try to reduce their expenditure and although they target non-essential

healthcare first, this often leads to misunderstandings and hardship.What is considered unnecessary by one person is seen as essential by another.

Principles to validate exclusions:

- Best practice

- Evidence-based healthcare

- Clinical protocol

- Cost-effectiveness (affordability)

- Laws of the country

Funds have sought to limit their liability by financial limitations and/or limitations or even exclusions on cover for certain conditions or treatments.

The exclusion list of scheme options (Annexure C of scheme rules) deals with limitations of entitlements. Schemes must ensure that there is good reason for these exclusions and limitations, and that they are not too broadly worded. Otherwise, they may lead to arbitrary or unreasonable denial of care.

Financing available for healthcare is not infinite. Debates on fair and equitable rationing in healthcare abound worldwide. A fair, transparent and scientifically justified system is necessary also in South Africa.

But why exclusions and limitations?

Entitlements in any option are discretionary (optional) or non-discretionary (compulsory). The latter are covered by the prescribed minimum benefits (PMBs). The Regulations in the Medical Schemes Act 131 of 1998 deal with the entitlement

to PMBs: they must be paid in full under certain circumstances, such as when the member obtained the service from a designated service provider. The standard of care (and entitlement to it) is determined by protocols based on the

principles of evidence-based medicine or, where these do not exist, the protocols of the public sector. Non-PMB conditions and entitlements are dealt with in scheme rules, and limitations and exclusions are applicable to them.

Exclusions

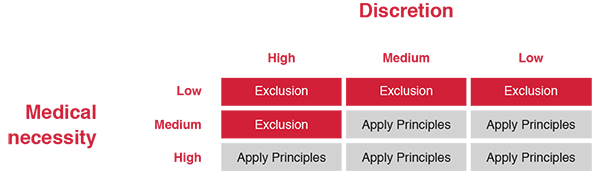

The following principles should be considered when deciding whether an exclusion is justified or not: best practice, evidence-based healthcare, clinical protocol, cost-effectiveness (affordability), and the laws of the country.Conditions or circumstances that should definitely not be excluded are those that are medically necessary, with little discretion from the member and/or service provider. Put differently, consider whether urgent treatment is needed to prevent death or permanent disability, and whether the attending doctor has some discretion as to the timing of treatment, and whether the treatment should be given at all. It would, for example, be entirely inappropriate to include an exclusion for the treatment of acute appendicitis, whereas an exclusion for cosmetic surgery in the absence of clinical indications would be appropriate. Not forgetting affordability, clinical protocols based on evidence-based medicine should be the bottom line when deciding whether funding is justified or not.

Limitations

Fair exclusion? You decide.

Most schemes exclude obesity management from their cover. Is this fair?

Obesity can be seen as a lifestyle condition that the patient can deal with on his/her own even though the medium- to long-term outcomes of managing this condition are often disappointing.

But if a patient suffers from morbid obesity, evidence shows that (s)he is likely to suffer from substantial morbidity and may eventually die from this. Gastric bypass procedures are sometimes the only solution.

Many provisos are applicable, which must be accommodated in a protocol, but it seems unfair to allow morbid obesity to be excluded. What do you think?

Limitations on cover are appropriate where they permit a degree of financial risk management. But they are inappropriate where their application allows for the selective targeting of specific people or vulnerable risk groups.

Thus, reasonable financial management should be permitted, but not to the extent that it allows risk selection and unfair discrimination.

Limitations should be permitted where they achieve the following:

- reasonable cost-sharing with members for healthcare services where the demand for these services is subject to high member discretion; and

- reasonable cost- sharing with members for healthcare services that are routine and consequently do not require insurance.

This refers to discretionary services that are used so routinely that contributions tend to equal what the member would have paid from his/her own pocket.

Limitations are inappropriate where they achieve the following:

- cost-sharing with members for healthcare services that are non-discretionary and determined by the healthcare provider; and

- cost-sharing with members for healthcare services that are costly and infrequent